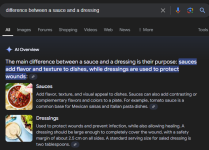

Gotta love the AI generated info that show up at the top of the search results these days. I reference to this song, the AI summary starts as follows (with my emphasis added.)They don't see / Whole Foods

-Tank and the Bangas

Become a Patron!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Spin Off of Keep a Word/Drop a Word and Music, Pics, and Whatnot

- Thread starter 2WhiteWolves

- Start date

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

Bad to the Bone - George Thorogood & The Destroyers

Going off band nameBad to the Bone - George Thorogood & The Destroyers

Destroyer - The Kinks

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT

You Really Got Me- The Kinks

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT

It is storming terrible up here in Western NY! Windy,cold,pouring rain, yuck!

I have been losing power and internet on and off all night into the morning. Wednesday I get my automatic house generator , I can hardly wait, no more worries on losing power I hope! Plus I pick a really bad day to bring my car in for repairs,ugh!

I have been losing power and internet on and off all night into the morning. Wednesday I get my automatic house generator , I can hardly wait, no more worries on losing power I hope! Plus I pick a really bad day to bring my car in for repairs,ugh!

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT

My Oh My- Slade

Gotta love the AI generated info that show up at the top of the search results these days.

I'm fed up with having the AI search results shoved at me without having asked for them. We are blamed for using up the world's resources, and being targeted for schemes like the 15-minute cities, yet AI is imposed on us as if it were anything real, but is an absolute resource gobbler:

The AI Boom Could Use a Shocking Amount of Electricity

Powering artificial intelligence models takes a lot of energy. A new analysis demonstrates just how big the problem could become

AI Is Accelerating the Loss of Our Scarcest Natural Resource: Water

With the rise of generative AI, companies have significantly raised their water usage, sparking concerns about the sustainability of such practices.

www.forbes.com

www.forbes.com

Those are not the only descriptions I've seen of how much more electricity is used by AI than just the normal search for references, how water rights are being taken from farmers with the underhanded "climate change" accusation, while their water is being diverted to AI plants.

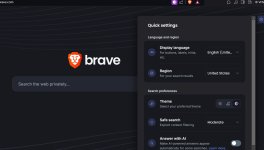

Here are a couple of shots of how to get rid of the unchosen AI search response, but you have to do it every time.

On this one, see the gear icon on the upper right, underneath the letters "VPN":

This shot shows some of what you get when you click that gear, and where you can turn off the AI response:

I stumbled onto Tank and the Bangas when I went to Allmusic.com to look up something else. It was featured on the home page among other new releases.

I saw the title and my first thought was "There has to be a story behind that" which is what led to my search. Yes, AI needs far too much electricity and I also dislike the AI generated search overviews, but they are sometimes humorous.I stumbled onto Tank and the Bangas when I went to Allmusic.com to look up something else. It was featured on the home page among other new releases.

Excuse my French

-Caro Emerald

-Caro Emerald

It is storming terrible up here in Western NY! Windy,cold,pouring rain, yuck!

I have been losing power and internet on and off all night into the morning. Wednesday I get my automatic house generator , I can hardly wait, no more worries on losing power I hope! Plus I pick a really bad day to bring my car in for repairs,ugh!

I hope it all smooths out for you soon Snap.

Artist match since I am currently enjoying exploring her work.Excuse my French

-Caro Emerald

You Don't Love Me - Caro Emerald

Don't lick my leg

-Stikky

-Stikky

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

Lick and a Promise - Aerosmith

Roses and promises

-Benjamin Biolay

-Benjamin Biolay

Good still mornin Family

I hope everyone is havin a great day

Native American Totem Pole

Ketchikan, Alaska

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from large trees, mostly Western Red Cedar, by cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. The word totem is derived from the Ojibwe word odoodem, "his kinship group".

History

Being made of cedar, which decays eventually in the rainforest environment of the Northwest Coast, few examples of poles carved before 1900 exist. Noteworthy examples include those at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, BC and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC in Vancouver, BC, dating as far back as 1880. And, while 18th century accounts of European explorers along the coast indicate that poles certainly existed prior to 1800, they were smaller and few in number. In all likelihood, the freestanding poles seen by the first European explorers were preceded by a long history of monumental carving, particularly interior house posts. Eddie Malin has proposed that totem poles progressed from house posts, funerary containers, and memorial markers into symbols of clan and family wealth and prestige. He argues that pole construction centered around the Haida people of the Queen Charlotte Islands, from whence it spread outward to the Tsimshian and Tlingit, and then down the coast to the tribes of British Columbia and northern Washington. This is supported by the photographic history of the Northwest Coast and the deeper sophistication of Haida poles. The regional stylistic differences between poles would then be due not to a change in style over time, but to application of existing regional artistic styles to a new medium. Early-20th-century theories, such as those of the anthropologist Marius Barbeau who considered the poles an entirely post-contact phenomenon made possible by the introduction of metal tools, were treated with skepticism at the time and are now discredited.

The disruptions following American and European trade and settlement first led to a flowering and then to a decline in the cultures and totem pole carving. The widespread importation of iron and steel tools from Britain, the United States and China led to much more rapid and accurate production of carved wooden goods, including poles. It is not certain whether iron tools were actually introduced by traders, or whether iron tools were already produced aboriginally from drift iron recovered from shipwrecks; nevertheless the presence of trading vessels and exploration ships simplified the acquisition of iron tools whose use greatly enhanced totem pole construction. The Maritime Fur Trade gave rise to a tremendous accumulation of wealth among the coastal peoples, and much of this wealth was spent and distributed in lavish potlatches frequently associated with the construction and erection of totem poles. Poles were commissioned by many wealthy leaders to represent their social status and the importance of their families and clans. By the 19th century certain Christian missionaries reviled the totem pole as an object of heathen worship and urged converts to cease production and destroy existing poles.

Totem pole construction underwent a dramatic decline at the end of the 19th century due to American and Canadian policies and practices of acculturation and assimilation. In the mid-20th century a combination of cultural, linguistic, and artistic revival along with intense scholarly scrutiny and the continuing fascination and support of an educated and empathetic public led to a renewal and extension of this moribund artistic tradition. Freshly-carved totem poles are being erected up and down the coast. Related artistic production is pouring forth in many new and traditional media, ranging from tourist trinkets to masterful works in wood, stone, blown and etched glass, and many other traditional and non-traditional media.

Today a number of successful native artists carve totem poles on commission, usually taking the opportunity to educate apprentices in the demanding art of traditional carving and its concomitant joinery. Such modern poles are almost always executed in traditional styles, although some artists have felt free to include modern subject matter or use nontraditional styles in their execution. The commission for a modern pole ranges in the tens of thousands of dollars; the time spent carving after initial designs are completed usually lasts about a year, so the commission essentially functions as the artist's primary means of income during the period. Totem poles take about 6–12 months to complete.

I hope everyone is havin a great day

Native American Totem Pole

Ketchikan, Alaska

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from large trees, mostly Western Red Cedar, by cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. The word totem is derived from the Ojibwe word odoodem, "his kinship group".

History

Being made of cedar, which decays eventually in the rainforest environment of the Northwest Coast, few examples of poles carved before 1900 exist. Noteworthy examples include those at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, BC and the Museum of Anthropology at UBC in Vancouver, BC, dating as far back as 1880. And, while 18th century accounts of European explorers along the coast indicate that poles certainly existed prior to 1800, they were smaller and few in number. In all likelihood, the freestanding poles seen by the first European explorers were preceded by a long history of monumental carving, particularly interior house posts. Eddie Malin has proposed that totem poles progressed from house posts, funerary containers, and memorial markers into symbols of clan and family wealth and prestige. He argues that pole construction centered around the Haida people of the Queen Charlotte Islands, from whence it spread outward to the Tsimshian and Tlingit, and then down the coast to the tribes of British Columbia and northern Washington. This is supported by the photographic history of the Northwest Coast and the deeper sophistication of Haida poles. The regional stylistic differences between poles would then be due not to a change in style over time, but to application of existing regional artistic styles to a new medium. Early-20th-century theories, such as those of the anthropologist Marius Barbeau who considered the poles an entirely post-contact phenomenon made possible by the introduction of metal tools, were treated with skepticism at the time and are now discredited.

The disruptions following American and European trade and settlement first led to a flowering and then to a decline in the cultures and totem pole carving. The widespread importation of iron and steel tools from Britain, the United States and China led to much more rapid and accurate production of carved wooden goods, including poles. It is not certain whether iron tools were actually introduced by traders, or whether iron tools were already produced aboriginally from drift iron recovered from shipwrecks; nevertheless the presence of trading vessels and exploration ships simplified the acquisition of iron tools whose use greatly enhanced totem pole construction. The Maritime Fur Trade gave rise to a tremendous accumulation of wealth among the coastal peoples, and much of this wealth was spent and distributed in lavish potlatches frequently associated with the construction and erection of totem poles. Poles were commissioned by many wealthy leaders to represent their social status and the importance of their families and clans. By the 19th century certain Christian missionaries reviled the totem pole as an object of heathen worship and urged converts to cease production and destroy existing poles.

Totem pole construction underwent a dramatic decline at the end of the 19th century due to American and Canadian policies and practices of acculturation and assimilation. In the mid-20th century a combination of cultural, linguistic, and artistic revival along with intense scholarly scrutiny and the continuing fascination and support of an educated and empathetic public led to a renewal and extension of this moribund artistic tradition. Freshly-carved totem poles are being erected up and down the coast. Related artistic production is pouring forth in many new and traditional media, ranging from tourist trinkets to masterful works in wood, stone, blown and etched glass, and many other traditional and non-traditional media.

Today a number of successful native artists carve totem poles on commission, usually taking the opportunity to educate apprentices in the demanding art of traditional carving and its concomitant joinery. Such modern poles are almost always executed in traditional styles, although some artists have felt free to include modern subject matter or use nontraditional styles in their execution. The commission for a modern pole ranges in the tens of thousands of dollars; the time spent carving after initial designs are completed usually lasts about a year, so the commission essentially functions as the artist's primary means of income during the period. Totem poles take about 6–12 months to complete.

Don't make promises you can't keep

I'm the keeper of dogs and cats

-Carol Cisneros

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT

Keep Your Hands To Yourself- Georgia Satellites

Hand of God

-Nick Cave, Warren Ellis

-Nick Cave, Warren Ellis

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

50,000 Miles Beneath My Brain - Ten Years AfterBrain damage

One of my favorites

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

Had my monthly Master Gardener meeting this morning. And since I was over there I made trip to Costco. We don't have one in my town.

We're lucky we have a costco here, I wish they had more organic stuff but I do get quite a bit thereHad my monthly Master Gardener meeting this morning. And since I was over there I made trip to Costco. We don't have one in my town.

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

Come Sail Away - Styx

We're lucky we have a costco here, I wish they had more organic stuff but I do get quite a bit there

They're getting more and more organic lately. Costco is the only source I know of for organic Rotels and organic Wholly Avocado (just smashed avo & salt). They have tons of organic fruit and veg, organic tortilla chips, pretty much everything I want:

Strawberries, blackberries, raspberries, mini watermelons, cantaloupe, blueberries, mushrooms, brussels sprouts, apples, cucumbers, butternut squash, broccoli, carrots, zucchini, kiwi, celery, mini sweet peppers, tomatoes on the vine, baby spinach, spring mix, organic dried fruit. I wish the regular grocery stores would do that well with the organics, because other than fruit and veg, Costco's schtick is that you have to buy such large amounts.

I don't buy all that at one time, but I scrambled to take a look after reading your post.

Now it may not be the same where you are Jimi, if there are shipping/delivery issues there.

I should have told Goph, Costco has the most beautiful, perfect bouquets of two dozen roses for 20.00, which disappeared during the Covid lockdown era for a couple of years, but they're back, and so beautiful. In case he's been sassing his wife.

They also still have the true French champagne privately labeled for them. It is soooooo good.

Last edited:

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

Yard Sale - Alex Warren

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

Been busy catching up with the billions of emails I got while I was away today, and now I have another meeting to go to. TTFN

They must be behind the times hereThey have tons of organic fruit and veg, organic tortilla chips, pretty much everything I want:

gopher_byrd

Cranky Old Fart

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

ECF Refugee

Member For 5 Years

VU Patreon

School - Supertramp

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT

Girl School- Britny Fox

SnapDragon NY

Senior Moderator

Staff member

Senior Moderator

VU Donator

Diamond Contributor

Press Corps

Member For 5 Years

VU SWAT