*-- Study confirms cases of human-to-cat COVID-19 transmission --*

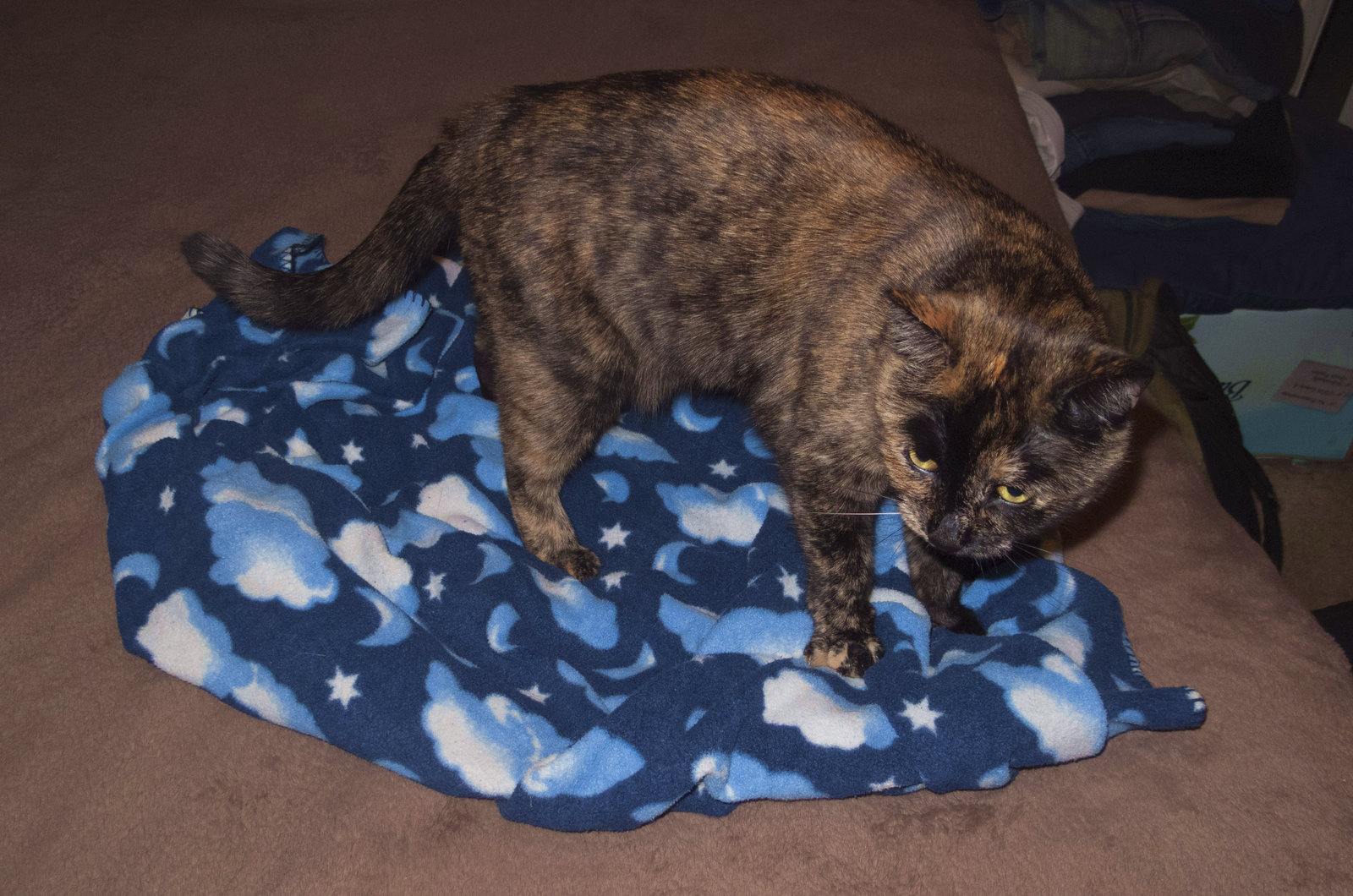

People infected with COVID-19 who have cats as pets can pass the virus to their feline companions, and the felines may develop life-threatening respiratory symptoms, a study published Friday by Vet Record found.

In an assessment of two cats in Britain that lived in households with infected people and developed symptoms of the virus, one cat, 4 months old, developed severe pneumonia and died, the researchers said.

The other cat, 6 years old, had cold-like symptoms, as well as conjunctivitis, or "pink eye," but survived.

Each of the infected cats, along with nine other cats diagnosed with the virus globally, shared no feline-specific genetic strains of the virus, according to the researchers.

"Our findings indicate that human-to-cat transmission of [the coronavirus] occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.K., with the infected cats displaying mild or severe respiratory disease," study co-author Dr. Margaret J. Hosie told UPI in an email.

"Given the ability of the coronavirus to infect companion animals, it will be important to monitor for human-to-cat, cat-to-cat and cat-to-human transmission" as the pandemic continues, said Hosie, a professor of comparative virology at the University of Glasgow Center for Virus Research in Scotland.

Through the end of March, 14 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in household pets have been reported globally -- three in dogs and 11 in cats --according to figures from the World Health Organization.

Although no evidence exists that animals play a significant role in spreading the virus to people, it appears that it can spread from people to animals, especially during close contact, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

An outbreak of COVID-19 occurred at mink farms in Denmark last fall, however, and fears that the strain involved could spread to humans led to millions of the animals being euthanized.

To date, "we have no sense of how common [human-to-animal spread] is," veterinary medicine specialist Shelley C. Rankin, who was not part of the cat study, told UPI in an email.

"We do know that animals in contact with infected humans are at risk and that the virus can be transmitted to them and in some cases can cause infection and clinical signs," said Rankin, a professor of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine in Philadelphia.

For their research, Hosie and her colleagues analyzed samples collected from the 4-month-old female domestic cat, as well as those from 387 felines living in homes with people with confirmed COVID-19.

The second infected cat, the 6-year-old, was found in this latter group, the researchers said.

The 4-month-old cat first developed respiratory symptoms, including a cough and shortness of breath on April 11, 2020, after a person in the home developed COVID-19-like illness at the end of March.

The owners brought the cat to a veterinarian on April 15, 2020, at which point she was having difficulty breathing.

Because her condition worsened, with severe damage to the lungs, she was euthanized one week later, they said.

The 6-year-old cat, also a female, developed cold-like symptoms, including a cough and runny nose, as well as conjunctivitis, known as "pink eye," which causes redness and inflammation underneath the eyelid and in the "whites" of the eyes, according to the Mayo Clinic.

This older cat's symptoms resolved on their own, and a second cat living in the same home did not test positive for the virus, Hosie and her colleagues said.

"Human-to-cat transmission appears to occur rarely," Hosie told UPI.

"We tested over 350 respiratory samples from cats before we identified one that tested positive," she said.

Still, based on these findings, pet owners who experience symptoms of COVID-19 should take steps to avoid passing the virus to their companion animals, Hosie and Rankin said.

"If you have COVID-19, then you should minimize contact with your pets as much as possible," Rankin said.

However, "the number of documented cases don't suggest that a vaccine for companion animals is currently necessary [and] I don't think that will change any time soon," she said.